How Shopify and ecommerce fulfillment created the new mom and pop revolution

Written by Darius Banasik

January 24, 2020

Resources

Retail has undergone a series of revolutions in the past century, with the latest being perhaps the most surprising, as consumers turn away from superstores in favor of a new kind of mom and pop store. The advent of the internet, and the huge success of ecommerce, has enabled countless small enterprises to compete on a global stage on a scale never seen before. Ecommerce platforms like Shopify have led this revolution, allowing small businesses to set up shop and sell internationally.

A burgeoning fulfillment industry has helped these new companies warehouse and ship their products, outsourcing all aspects of ecommerce and enabling vendors to set up remote stores without even handling their products.

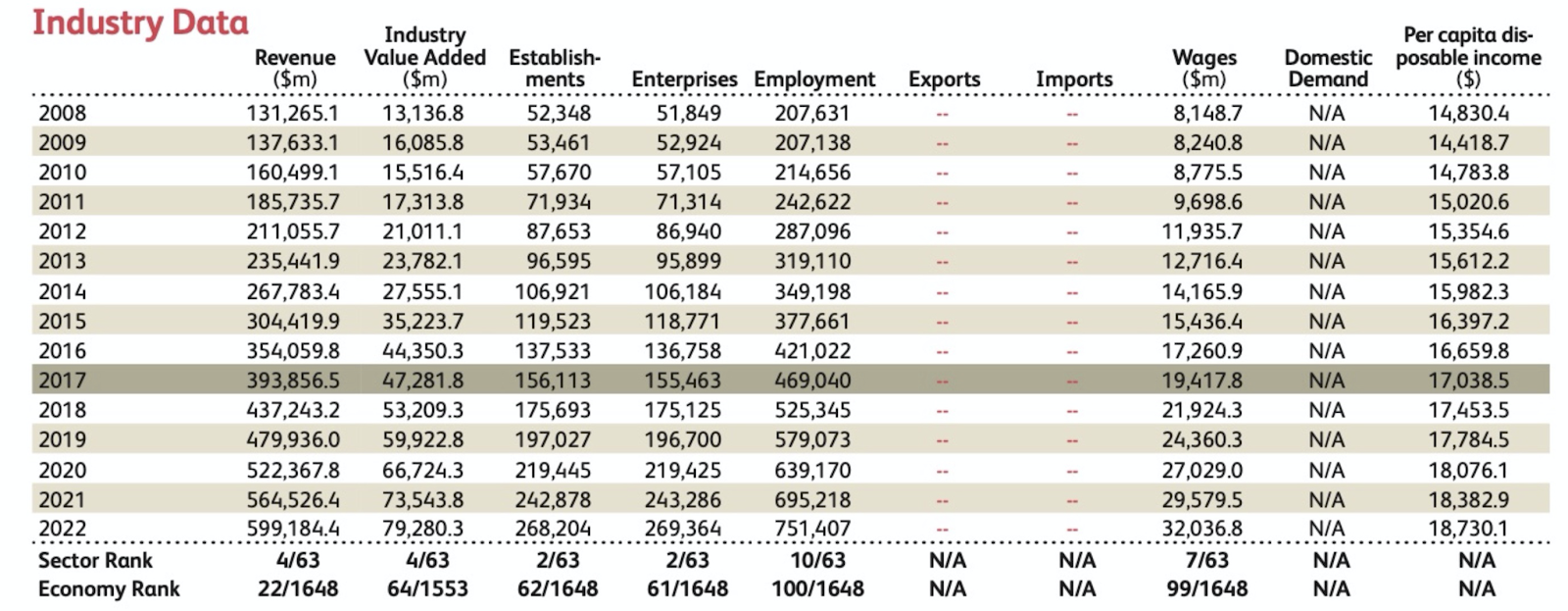

This industry shift is reflected in data from IBISWorld, which shows that even as more ecommerce establishments are entering the market, the average number of employees per enterprise is falling, from 3.97 employees in 2008, to a predicted 2.80 by 2022. Across the decade from 2008-2018, the total number of ecommerce enterprises increased by more than 335 percent, while employee numbers only grew by 250 percent, reducing the ratio of employees per enterprise by almost a quarter.

So what’s fueling this drive toward smaller outfits and sole traders? Rapid technological advances, coupled with changing social demographics, and political and economic considerations, have paved the way for a new golden age of “mom and pop” stores that flourish online and are run by the younger generation, not their parents.

End of the old mom and pops

To understand this trend, we have to look back as far as the end of World War II, when mom and pop stores dominated the American high street and logistics constraints kept businesses local. With the return of G.I.s, a booming population, and surging manufacturing industry, the American public was more affluent, and consumer goods more affordable, than at any other period in modern history.

Through the 1950s, more than 58 million automobiles were manufactured and sold in the United States—one for every three people, or more than one car per family. With cars came greater mobility, and a rise in housing developments as suburbs began to appear around major cities. Thanks in part to the G.I. Bill, which enabled returning servicemen to purchase homes with low down payments and interest rates, almost 1.5 million new homes were built every year from 1946 to 1955. That’s 4.5 times more homes than were built each year in the preceding 15 years since 1930.

With suburbs came shopping malls: dedicated spaces that catered to a newly car-dependent population. As well as offering families the convenience of a centralized location to do all their shopping, they also provided an opportunity for chain stores to flourish. With improved transport and logistics networks, and better communications systems facilitating interstate commerce, nationwide chains began to emerge. Walmart, Ace Hardware, Dick’s Sporting Goods, Dollar General, Publix, and Toys “R” Us are just some of the stores that were founded or expanded in the post-war era, and dominated the American retail market for the next half-century.

The rise of online retail

In 1994, Jeff Bezos founded Amazon.com in Bellevue, Washington. The company, an online bookstore, went public in 1997 and began to diversify its stock to include music and videos the following year. In the two decades since, Amazon has become a global powerhouse, surpassing Walmart as the most valuable retailer in the United States by market capitalization in 2015.

As larger stores failed to understand the significance of the internet to the future of retail, Amazon aggressively worked to corner the emerging market of online shoppers, undercutting long-established stores with a huge inventory that no brick and mortar location could profitably carry. In 2000, Amazon boosted its inventory further by opening Amazon Marketplace, allowing third-party sellers to retail goods through the Amazon store.

Amazon didn’t create the first online marketplace—eBay was founded as AuctionWeb in 1995—but it did herald the start of a new era in online retail. Suddenly small and independent businesses could manufacture and sell goods directly to consumers, paying only a small commission to get their products listed on the world’s biggest and most trusted online store.

Garage sales to global enterprise

The first digital marketplaces were little more than glorified garage sales—spaces where individuals could sell old possessions and unwanted Christmas presents. Small businesses began to emerge, with resellers sourcing inventory from thrift stores and high street sales, or buying out limited edition items and selling at a premium once the original retailer had sold out.

Because the internet provided a national or global audience for online sellers, small-scale craftspeople and manufacturers also gained a foothold. Etsy, founded in 2005, opened up a new marketplace for artists, wood- and metalworkers, fabric crafters, and more. Startups could also sell their products online, mitigating showroom and advertising costs.

With a rise in small-scale sellers, new payment aggregators began to emerge. PayPal launched in 1998, and was followed by numerous others, including Payoneer (2005), Amazon Payments (2007), Square (2009), Dwolla (2010), and Stripe (2011). By acting as an intermediary between parties in online transactions, payment processing companies boosted consumer confidence in online shopping and enabled individuals and small enterprises to accept multiple payment methods.

At the same time, websites were becoming easier to create. WordPress launched in 2003 and developed plugin architecture in 2004, meaning anyone could create an ecommerce website with very little technical know-how. WooCommerce, a dedicated WordPress ecommerce plugin, was launched in 2011 and quickly became one of the service’s most popular plugins. Today it has almost 59 million active installations, helping online sellers retail to customers around the world.

According to data from eBay Inc., over 90 percent of U.S. businesses using their site are selling abroad, to an average of 30 different countries. This far surpasses traditional business models favored by established retailers, only five percent of which trade across borders, and to fewer than five countries.

Where large retailers have struggled to find fulfillment solutions, small businesses have fueled a boom in logistics companies. Once seen as the enemy of the Post Office, the internet, via online shopping, has led to a shipping renaissance. Every item sold online has to shipped, and that increase in volume is making dramatic changes to the logistics industry. Parcels comprised less than 10 percent of global postal service revenue in 2002. Ten years later, that figure had doubled. The IPC Global Postal Industry Report 2019 showed that parcel volumes increased by 9.1 percent in 2018, and concluded that ecommerce was “the driving force of postal industry growth” worldwide.

The great equalizer

The availability of online marketplaces and logistics and fulfillment providers has enabled small businesses to compete on equal ground—and even to some advantage—against established brick and mortar retailers. In 1998, the U.S. Census Bureau recorded ecommerce as 0.2 percent of total retail sales. By 2019, the online shopping industry had grown to capture 11.2 percent of the retail market.

Large retailers were slow to respond to the shift in consumer behavior. Department stores such as JC Penney and Sears have struggled—or failed—to survive in the digital age. With extensive inventories and established supply chains, creating websites with the technology to display and retail products is a vast and costly undertaking. Shipping logistics, warehousing, and pricing strategies all delayed the move for many retailers, giving online-only startups and sole traders an advantage they continue to capitalize on.

The Shopify effect

In 2004, three Canadian business partners opened an online snowboarding equipment store, Snowdevil. Tobias Lütke, Daniel Weinand, and Scott Lake were frustrated by how difficult available ecommerce solutions made the process of creating a storefront and shopping cart system. Lütke, a computer programmer, decided to build his own software using an open source web application framework. Realizing the potential of what he’d created, the Snowdevil team turned their attention to ecommerce and launched Shopify in June 2006.

Lütke, Weinland, and Lake typified the new wave of retail entrepreneurs finding success in ecommerce. Young and computer-savvy, they saw the opportunity offered by the internet and used it to open their own store, following a similar model to traditional brick and mortar establishments. This was a logical progression from individuals selling unwanted possessions, or small-scale resellers sourcing products to sell on other companies’ marketplaces. By retaining control of all aspects of the shopping platform, small businesses could reap greater profits and have greater control over what and how they sold.

While eBay, Etsy, and Amazon Marketplace gave online sellers their first storefronts, they came with their own constraints and pitfalls. From ever-increasing fees for sellers, to restrictions on what sellers can and can’t offer, doing business on the world’s global marketplaces is more complicated than some retailers expected. There are other concerns too. After Amazon introduced on-site ads, many sellers found that to retain visibility and sell in the same volume, they had to pay extra for Amazon to show their products to consumers. And others discovered that Amazon penalized them with reduced visibility when their prices undercut competitors.

In a brick and mortar world, small businesses struggle to compete with established brands. The initial investment needed to lease retail space, and stock and staff a store, along with all the attendant red tape (licenses, insurance, tax, payroll…) is enough to drive most out of the market. Online, however, anybody can build a website and begin selling in a very short space of time, for a comparatively small outlay. The absence of major retailers in the online shopping space gave small businesses an opportunity to fill gaps in the market that don’t exist offline anymore, and high traffic from search engines gives small businesses who strike out alone a fighting chance against bigger, more established competitors.

Shopify enabled this process by providing the framework for new companies to get off the online marketplaces and set up their own storefronts, and it has proved a huge success. As of June 2019, it is used by over a million businesses across 175 countries. In 2018, Shopify’s total gross merchandise volume topped $41.1 billion.

Young entrepreneurs lead the way

The opportunities for success in small ecom businesses appeal particularly to the demographic most comfortable with ecommerce—the under-55s. Research by IBISWorld shows that in 2017, half of all online consumers were aged 35-54, and they spend the most of any age group, around $1800 per year. Younger consumers, 18-34, comprise over 27 percent of the ecommerce market, but economic instability and lower average incomes among 18-24-year-olds mean they spend considerably less than their older peers, 25-34, who spend around 60 percent more. These figures suggest ecommerce is an industry that will enjoy continued growth in correlation to the earning power of consumers already used to shopping online.

Younger people aren’t just purchasing goods online. Increasingly, ecommerce “mom and pop” stores are being founded and run by people in their thirties, twenties, or even teens. The top-earning YouTuber of 2019 is an 8-year-old, so perhaps it isn’t surprising that generations raised with the internet have been the fastest to see its money-making potential. Jeff Bezos was 30 when he founded Amazon, Pierre Omidyar 28 when he launched the website that became eBay, and the three co-founders of Etsy were in their early-to-mid-20s.

The appeal of ecommerce to a younger demographic has two likely roots: the low bar to entry, and the hands-off nature of online selling.

A study by Bankrate explored the phenomenon of the “side hustle”—an additional source of revenue generated from odd jobs, crafting, microtasking, or online selling. The figures show that while a large number of Americans (37 percent) have earned extra income from a side job, more than half of millennials (51 percent) report making money from a secondary source.

“When I talk to millennials, I think two things really come up. One is that they’re very aware that there’s no job security, so they’re the least likely generation to kind of settle into a full-time job and assume that everything’s going to be OK,” says Diane Mulcahy, author of The Gig Economy. “The other reason is clearly economic. Most millennials—at least on the professional end who have been to college—have significant debt and a lot of them are looking for ways to either build a financial cushion or reduce their debt faster.”

Lower wages, rising cost of living, decreased job security, and beginning their working lives in debt, are all drivers pushing the younger generation toward diversifying their income streams, seeking new opportunities to make money, and taking a proactive interest in carving out their own careers, rather than being beholden to an employer. The U.S. workforce saw a 50 percent increase in gig workers and freelancers in the decade to 2015, according to data from NACo. Self-employment rates rose by 19 percent in the same period, and almost a quarter of Americans reported earning income from the “digital economy” in 2016.

Under these circumstances, lucrative opportunities to earn money by selling online are rapidly being taken up by young entrepreneurs. Some get started without putting a penny down, for example artists who sell their designs on apparel and accessories using print on demand services that drop-ship directly to customers. Others buy low-cost inventory from overseas manufacturers and use warehousing and logistics suppliers to store and ship on their behalf, and even handle complaints and returns.

The ecommerce fulfillment effect

Online stores can be almost completely hands-off, allowing sellers to generate side income without burning out. Third-party logistics (3PLs) companies have stepped up to handle every aspect of ecommerce from the moment a sale is made, and the explosion of 3PLs in recent years saw the industry top $200 billion gross revenue in 2018.

The International Post Corporation (IPC) monitors postal operations in 25 countries as part of its mission to improve international mail services. The key findings in the IPC’s 2019 industry report show that while state-run mail carriers are experiencing a boom in business thanks to ecommerce, they’re being outstripped by a growing army of smaller competitors.

Globally, postal industry revenue reached €392.3bn in 2017, an increase of almost 2 percent on the previous year. However, all that growth came from parcels (up €9.0bn) and logistics (up €1.5bn). Mail revenue actually fell €3.2bn, as individuals and businesses continue to favor electronic communication.

International revenue accounted for almost a quarter of postal income in 2017, as shoppers take advantage of cheaper prices available overseas. The IPC noted that ecommerce was the main driver for growth “for both domestic and cross-border B2C volume,” and not just for state-run mail carriers. The logistics market saw a fourfold increase in volume in 2018, far oustripping the growth enjoyed by larger competitors.

Because of the booming marketplace of supply and fulfillment companies, online sellers can quickly scale their businesses without engaging many (or any) more staff. Jungle Scout recently surveyed over 2500 Amazon Marketplace sellers, 66 percent of whom reported five-figure monthly incomes after 18 months. More importantly, the survey found that startup costs had no significant statistical correlation with long-term profitability. With ecommerce, a side hustle can become a full-time business in a relatively short period, without many of the bars to entry that prevent young entrepreneurs from flourishing in other industries.

Looking toward a successful future

With all the data showing the ecommerce industry is only going to continue to grow, online sellers who are establishing successful small businesses continue to thrive in a landscape that remains competitive, despite the dominance of Amazon and the rise of chain stores entering the marketplace (finally) with attractive, functional websites and mobile apps. IBISWorld predicts the number of ecommerce enterprises to grow by more than 11 percent year-on-year through 2022, fueled primarily by sole operators.

Millennial and Generation Z consumers are also the driving force behind ethical consumerism, “buycotting” brands that fail to live up to their social or ecological standards. That’s bad news for industry giant Amazon, which has suffered bad press on a number of fronts, not least working conditions in its warehouses, tax payments, and its carbon footprint. A Nielsen survey found almost two thirds of millennials and Gen. Zs are willing to pay extra for products from socially responsible brands, and in a study commissioned by CompareCards, almost a third of 18-to-55-year-olds reported boycotting a company they’ve previously spent money on. This year social media campaigns urged consumers to boycott Amazon’s Prime Day, in solidarity with Amazon workers.

The aggressive business tactics that turned Amazon into the market leader could also spell trouble for its future. As mass-market appeal wanes and consumers tire of big businesses that report record profits while paying little to no tax and less than living wages, local, independent, and artisanal stores are flourishing, with 61 percent of millennials saying they planned to shop at more small businesses, and are prepared to pay more to do so.

This climate leaves the path wide open for online sellers to capitalize. The Jungle Scout survey of Amazon Marketplace sellers found that 59 percent saw increased profits by diversifying their sales platforms away from Amazon toward other ecommerce sites, and almost half (49 percent) saw a boost by building their own websites, most using prebuilt, customizable online store frameworks such as Shopify. Small businesses are once again taking America by storm, with young entrepreneurs and consumers leading the way.

“We are in the midst of a generational shift,” says Anne Mastin, executive vice president of retail real estate for Steiner + Associates. “Industry turbulence is less about the internet and more about boomers giving way to millennials as the key consumer demographic. Going forward, stores and formats will continue to need to evolve if they want to survive. That’s not new—that’s how it has always been in the retail world.”

While millennials are routinely accused of killing any number of industries, we can trace most of these complaints back to the economically unstable position of the younger generation, and the steps they’re taking to get ahead in a less certain world. These very factors are the same driving force growing the ecommerce industry and encouraging the rise of young entrepreneurs, from shifting social mores that eschew mass-market consumerism typified by department stores, to debt-avoidance strategies, rejection of traditional workplace hierarchies, and willingness to leave a company for better employment opportunities.

Young Americans are finding success in online commerce ventures, reviving the retail industry by returning to a more traditional business model of diverse small, independent operators. But unlike the mom and pop stores of their grandparents’ generation, they are trading in a global marketplace, expanding their businesses in a virtual world without borders. As the ecommerce industry continues to grow, young entrepreneurs and online sellers are primed for a successful future to rival the glory days of the superstores that put the original mom and pop stores out of business.

At ecomBLVD, we’re committed to helping small online sellers turbocharge their businesses. From logistics to marketing, we can connect you with pre-qualified 3PLs and service providers to help you trim costs, stay ahead of demand, and let your business grow. Visit ecomblvd.com today for your free consultation.

Would you like to be featured?

Related Articles

How to find an ecommerce fulfillment center — Ultimate Guide Part 1

How to find an ecommerce fulfillment center — Ultimate Guide Part 1Have you ever looked for a vendor whose service is supposed to make your life easier, but ended up more confused or disoriented after reading their proposal, especially when comparing it to their...

Online sellers are suffering from decision overload. Here’s how we fix it.

Online sellers are suffering from decision overload. Here's how we fix it.I have always been fascinated with the decision-making process and why individuals make the choices they do. In particular, I wonder how we overcome what psychologist Barry Schwartz calls the...